Bent Melchior was born in 1929 to Danish parents in Beuthen, Germany (now Bytom, Poland), where his father Marcus held a Rabbinical post. His family moved back to Denmark in 1933, and. in 1943, during the Nazi German occupation of Denmark, Bent’s father, Rabbi Marcus Melchior was instrumental in saving Danish Jews...

Bent

Melchior

Stage 6 - Polarization

Bent Melchior was born in 1929 to Danish parents in Beuthen, Germany (now Bytom, Poland), where his father Marcus held a Rabbinical post. His family moved back to Denmark in 1933, and. in 1943, during the Nazi German occupation of Denmark, Bent’s father, Rabbi Marcus Melchior was instrumental in saving Danish Jews...

Bent Melchior

Bent Melchior was born in 1929 to Danish parents in Beuthen, Germany (now Bytom, Poland), where his father Marcus held a Rabbinical post. His family moved back to Denmark in 1933, and. in 1943, during the Nazi German occupation of Denmark, Bent’s father, Rabbi Marcus Melchior was instrumental in saving Danish Jews. That year, the family fled Copenhagen with the assistance of many ordinary non-Jewish Danes and after a perilous journey at sea arrived in Sweden, where they lived as refugees until the Danish liberation in 1945.

Bent Melchior received a Ph.D. from Copenhagen University at 21 years of age, and after a period as a teacher had his Rabbinical education in London. When his father passed away in 1969, he succeeded him as Chief Rabbi of Denmark, a position he held until 1996.

Bent was a human rights activist, prolific speaker and writer in the Danish community and media. In 2008, he became the first and only honorary member of the Danish Refugee Council and was an associate professor in Classical Hebrew literature at the University of Copenhagen from 1971 to 1984. Additionally, he acted as the President for B’nai B’rith Europe from 1993 to 1999 and as chairman of the board of the Centre for Dialogue “Brobyggerne” (Bridge Builders), which he co-founded with a former member of Danish Parliament Özlem Cekic. Bent has written numerous articles and books on issues relating to religion, Judaism and refugees and continued to be an outspoken advocate for the rights and conditions of refugees in Denmark until his passing in 2021. Bent’s son Michael was the chief Rabbi of Norway and his grandson Jair is currently the chief rabbi of Denmark.

Polaryzacja

Używając nienawistnej propagandy ekstremiści dzielą ludzi, a tych, którzy nie są ich zwolennikami nazywają zdrajcami lub sympatykami wroga i głoszą zasadę: „Jeśli nie jesteś z nami, jesteś przeciwko nam”. Przez takie działania tworzą się zazwyczaj dwa obozy – osoby przeciwstawiające się i popierające rozwiązanie danego problemu społecznego. Proces polaryzacji bardzo często przyczynia się do wybuchu i eskalacji konfliktów społecznych. Osoby o umiarkowanych poglądach, będące członkami grupy sprawców mają największe możliwości powstrzymania ludobójstwa, dlatego też zwykle są aresztowane i mordowane jako pierwsze. Grupa dominująca ustanawia dla siebie nieograniczoną władzę wprowadzając stany wyjątkowe lub rządząc za pomocą dekretów, znosząc prawa i wolności obywatelskie. Grupa ofiar jest rozbrajana, by nie mogła się bronić i by grupa dominująca mogła przejąć pełną kontrolę. Aby nie dopuścić do polaryzacji należy wspierać grupy i organizacje działające na rzecz praw człowieka oraz wprowadzić międzynarodowe sankcje.

How does this person’s story illustrate response to the particular stage of genocide in Dr. Stanton’s theory?

Bent Melchior’s story perfectly shows the danger of polarization. At this stage, society is divided into opposing groups: “us” and “them,” “the others,” e.g. Danes andJews. The courageous acts of ordinary Danes are an example of resistance to this artificial classification. The Jews of Denmark were well integrated into Danish society and had good connections to the general population based on common progressive and democratic values imbued in the educational and political life of the country and decades of shared experiences. In addition, an inclusive Danish social system, developed after World War I, greatly reduced class conflicts and allowed for the continuous integration and assimilation of the Jewish community, which essentially made the division into “us” and “them” impossible.

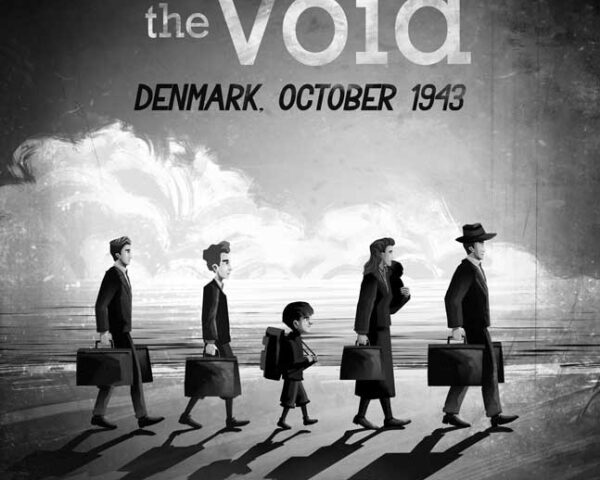

The animated short film Voices in the Void follows the Melchior family’s story during World War II in occupied Denmark and their escape to Sweden, thanks to the assistance of their Danish compatriots, particularly clergy and fishermen. The story is narrated by Bent, who was 14 at the time of his family’s escape. Despite the existential risks, thousands of Danes refused to abandon their Jewish neighbors. Later in life, many expressed that they did not view themselves as heroes, but rather as regular people who did what they had to do.

The Danish Exception

Denmark, forced into war in April 1940, was prepared for defeat and provided little resistance to the German invasion. The war was over in sixteen hours. The government surrendered after incurring little damage. Denmark became a collaborating country—an Aryan-like country that did not incite the racial hatred of the Germans. The king did not flee for his life or express outspoken opposition. The Danish government continued to function under the light hand of German authority. The king and government disowned and discouraged acts of sabotage on the part of small, besieged Resistance movements.

However, the Danes—the king, civil servants, and population—threatened outright opposition if the Jews in Denmark were isolated or punished. Conditions were met: from 1940 to 1943, Jews led utterly normal lives, no different from their Christian neighbors, avoiding the calamitous fate of other Jews throughout Europe.

The turning point for the Jews in Denmark came in the summer of 1943 when German authorities insisted that the Danish government execute their countrymen who were in the Resistance movement. The Danes would not turn on their own—except against the Communists. The Danish government resigned and abdicated authority to the Germans. In August and September, the nation turned toward the underground and gave widespread support to the Resistance forces. The Germans abandoned the so-called “model protectorate,” took control of the government, and moved to capture all the Jews in Denmark.

On September 29, two days before the projected roundup on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, Marcus Melchior, the acting chief rabbi of the Krystalgade synagogue, implored his stunned congregants and the whole Jewish community to go into hiding immediately. Two passenger ships, docked in Copenhagen’s port, were ready to ship approximately five thousand Jews to Germany on their way to Theresienstadt. Buses were to take the remaining two thousand. Suddenly Danish Jews, who had made few preparations for a possible roundup, had to flee. Decisions had to be made in a matter of hours and days about the dangers ahead: the safety of fleeing with infants and young children; whom to trust along the treacherous routes of escape.

Fortunately, Danish Christians were ready to face the danger that faced the Jews. From all strata of Danish society and in all parts of the country, clergymen, civil servants, doctors, nurses, students, store owners, farmers, fishermen, and teachers protected the Jews. First hidden in hospitals, homes, churches, and schools, the Jews were then guided by their compatriots through cities, villages, forests, and railroad stations to fishing boats in coastal towns. Funds were raised to pay fishermen who risked their boats and livelihoods to defy the Germans. At night, Jews were hidden in vessels and carried to safety in Sweden. With this extraordinary escape route at hand, in just a few weeks, 7,056 Jews fled to safety, as well as 686 non-Jewish spouses, 472 Jews were captured and sent to Theresienstadt for the duration of the war, but German leaders in Denmark agreed that none of the Jews would be sent east to the death camps. Danish civil servants and nongovernmental groups ensured the survival of the Jews in the camp by sending them food, vitamins, and clothing.

Within Europe’s formerly democratic nations that the Germans occupied, the Danish Jewish community was the only one that escaped devastation and destruction. Ninety-nine per cent of the Jewish population was rescued and survived the war years. Thus 6,500 Jews, refugees in Sweden after the escape from Denmark in 1943, returned to their homes two and a half years later to find the great majority of their homes and businesses intact. As Rabbi Bent Melchior, the former chief rabbi of Denmark has said: it was not unusual for Jews to have to leave their homes—in this, they were usually aided by others, eager to see them go. But to be welcomed home by their countrymen—that was unique!

What was it that made Denmark stand out from the background of other occupied countries in Europe? There was widespread frustration and anger within the Danish population over serving the German idea of the “model protectorate.” Progressive, democratic values strongly emphasized both group and individual responsibilities—attitudes that drew upon Danish Lutheran beliefs imbued in the educational and political life of the country. An inclusive Danish social system, developed after World War I, greatly reduced class conflicts and allowed for the continuous integration and assimilation of the small Jewish community. The persistent activities of Denmark’s small, tenacious Resistance movement, growing ever stronger by 1943, infuriated the German command. A conflicted German leadership in Denmark compromised its roundup of the Jews and enabled thousands to escape deportation to the East. And finally, the natural proximity of a country situated close to neutral Sweden, which by 1943 was willing to accept thousands of Jews as well as Danish insurgents in flight from the Germans, contributed to the rescue.

As rescuers, the Danes have a special claim to participate in Europe’s “restored humanity.” They defined empathy and defied indifference. The Danish story is overwhelmingly one of resistors and survivors through a collective national fight on behalf of a beleaguered and defenceless minority.