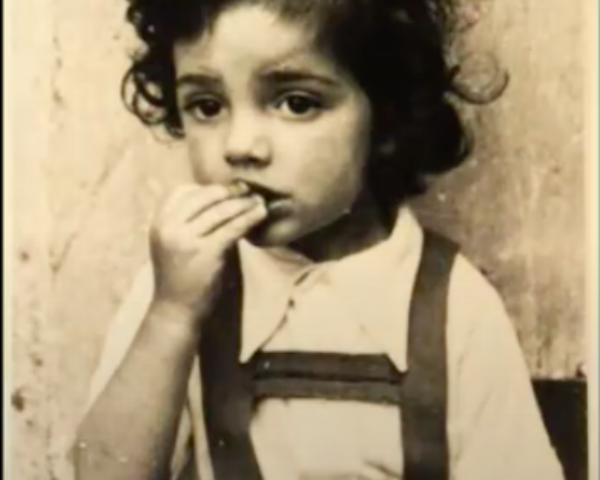

Peter Hein was born in February 1939 in the Netherlands. His parents, Netta and Paul Hein were German Jews who fled to the Netherlands in 1933, a few months after Hitler’s rise to power...

Peter Hein

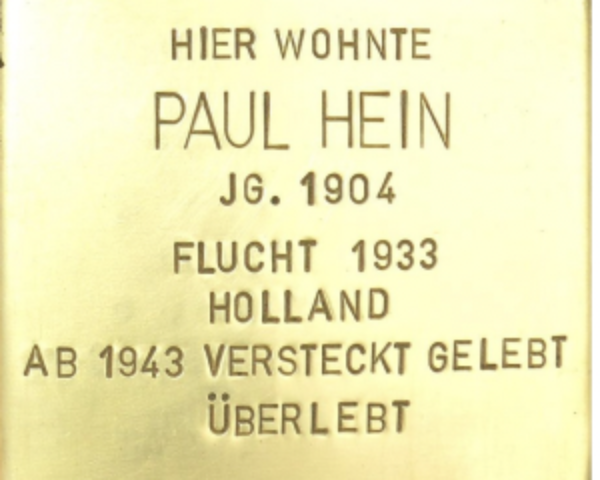

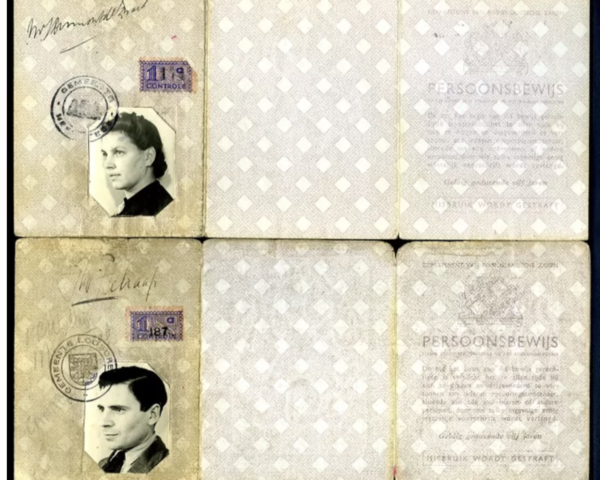

Peter Hein was born in February 1939 in the Netherlands. His parents, Netta and Paul Hein were German Jews who fled to the Netherlands in 1933, a few months after Hitler’s rise to power. Not before Paul was attacked and badly beaten by an antisemitic mob of his former colleagues. In the first years after the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, the small family were protected from deportation due to Netta’s severe case of tuberculosis. From mid-April 1943 until the end of the war Paul and Netta separated from Peter, their four-year-old son and went into hiding. Over the next two years, the couple hid in twelve different hiding places and with great courage and luck, succeeded to avoid capture. Peter was whisked from one hiding place to another. His name and appearance were changed and he was given a false backstory, claiming he was the son of Dutch settlers from the West Indies (then a Dutch colony) who had sent their son back to the Netherlands. Attachment became impossible, and he became very insular. By the time Peter reunited with his parents after the liberation of the Netherlands in May 1945, he could not remember them. Eventually, the family settled in Utrecht.

Peter became a doctor, an associate professor and senior lecturer of obstetrics and gynaecology at the University Nijmegen, married Hannah and had three children. More than 40 years after the war he sank into a severe depression as a consequence of his childhood trauma. He eventually overcame his depression, and today he is occupied with maintaining the memories of the fate of the Jews during WWII in the Netherlands and is disseminating knowledge concerning the Holocaust. He is a guest speaker throughout the country on these topics and on the effects of war trauma on his generation and the next ones. His three books and short stories have been published in Netherlands’ finest media. He is also a professional sculptor of bronze sculptures with several exhibitions a year in well-known galleries.

His son, David Hein, is the Head of the Defence Office of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers (KSC), an international court in The Hague tasked with adjudicating cases concerning international crimes committed in Kosovo before, during and after the war there.

Peter’s books:

The sixth year (2014) is the story about the unreal and confusing world of the seven-year-old Jewish boy Peter Hein who went from hiding place to hiding place during the Second World War without his parents. What does he understand about what happened to him? What was wrong with his dark eyes and black hair? In 1945 the war is over. But the post-war years are equally difficult. Family has died, there is no money, and life has to be picked up again. His parents are strangers to him. It feels like he’s hiding again. In The Sixth Year, Peter Hein impressively shows what war does to a child.

The people in hiding (2014)– The hiding of the parents of Peter Hein, at twelve addresses, turns out to be one long story of betrayal and escape, wanderings, despair, hunger, cold and betrayal again. The author also came across an undisclosed issue: his parents were accused of betraying a hiding place, which killed four people. After the war, Peter Hein’s mother only talked about the war, while his father avoided the subject. Hein wanted to clarify the whole story of his parents and interviewed them. In “De onderduikers” Hein tells the fascinating story of his parents in hiding and goes in search of the real traitor.

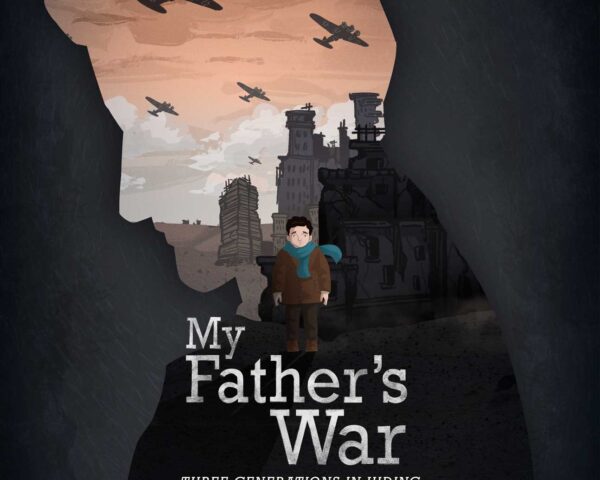

My Father’s War

The animated short film My Father’s War, produced by Humanity in Action, brings to life the experiences of Peter and his son David. As a Jewish toddler in the Netherlands in the 1940s, Peter was separated from his parents and whisked from hiding place to hiding place to escape deportation. From feigning scarlet fever to avoid a Nazi raid, to suffering crippling injuries during a bombing campaign, Peter somehow survives, one day at a time, even as capture and death surround him. Meanwhile, the film also follows Peter’s parents, who themselves must make a series of daring escapes as their hiding places are revealed to German forces and Dutch collaborators. By the end of the war, when Peter and his parents are finally reunited, Peter cannot even recognize them. But for Peter’s son David, his father’s war stories once sounded widely exciting, and as a child, David longs for the opportunity to experience similar exhilaration. What David did not realize is that, while his father’s physical injuries healed, a deep psychological trauma lingered. Eventually, Peter’s mental health buckles under the weight of his memories. The film thus explores the hereditary trauma of the Holocaust: the deep emotional wounds of forefathers passed on to children and grandchildren. Peter’s mental collapse jars David’s childhood and reveals to David the deep-seated impact conflict renders on those who suffer it. Ultimately, the experience inspires David to pursue a career bringing war criminals to justice. Narrated by both Peter and David, My Father’s War depicts an intergenerational conversation, reverberating across the decades.

The Netherlands – Jews during the war

When Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933, many Germans fled to the Netherlands. In 1939 a central internment camp was put up in Westerbork for those entering the country illegally. Soon after the outbreak of World War II that year, approximately 34,000 refugees entered the Netherlands.

Germany invaded the Netherlands on May 10, 1940; four days later, the Dutch army surrendered. Hitler soon ordered the establishment of a German civil administration. At that time, the Netherlands had a Jewish population of 140,000; 75,000 Jews lived in Amsterdam, and 15,000 were German Jews who had fled to the Netherlands believing it would stay a neutral country as it did in the Great War. A series of anti-Jewish measures began in the fall of 1940. In September, Jewish newspapers were shut down, and in November, all Jewish civil servants were fired. Soon the Germans began “Aryanization” by ordering all Jewish business owners to register their enterprises. During the summer of 1941, Jews were banned from public places, subjected to a night curfew and travel restrictions, thrown out of schools and universities, and had their art and property confiscated and plundered. In winter, the Germans opened forced labor camps. The Jewish badge was introduced in April 1942.

Deportations began in the summer of 1942. Jews were taken to Westerbork, and from there, to Auschwitz and Sobibor. A few Dutch rescue groups of students and of church circles came into being spontaneously and sporadically and helped find shelter for Jews, especially for children, but during the first and most crucial period of deportation, most Jews could only rely on themselves to find hiding places. The situation became more dangerous after September 1942, when special units were formed, made up of Dutch collaborators that began hunting for hiding Jews.

By April 1943 Jews were only allowed to live in Amsterdam, in the Vught and Westerbork camps. Organized and centrally coordinated Dutch resistance came into being that year after the Germans began to conscript Dutchmen for forced labor. By that time most of the Jews had already been deported. The last transport left the Netherlands in September 1944, By then, a total of 107,000 Jews had been deported to the extermination camps. Only 5,000 of them returned after the war. More than 75% of Dutch Jews perished in the Holocaust.

Some 25,000 Dutch Jews managed to go into hiding after being ordered to report for forced labor or deportation; about one-third were eventually discovered by the Germans, mostly with the aid of local informants. Many Jews were helped to hide by non-Jewish contacts who would help Jews move from hideout to hideout, and provide food, ration cards, and forged identity documents. All those who helped Jews were in danger of being deported to concentration camps.

Many children were also hidden with non-Jewish families; in all, 4,500 children were taken in, of whom only a few were discovered by the Germans.

(Adapted from Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies and Yad Vashem)

Persecution

In this stage, victims are forced to live in ghettos, deported to concentration camps, or detained in restricted areas, and are consequently sentenced to starvation as they are deliberately deprived of access to resources such as water, food, and medicine. Victims are also subjected to forced sterilizations or abortions; children are forcibly taken from their parents. A group of victims are systematically stripped of all rights, tortured and deported. Mass murders begin. The perpetrators watch closely to see if their actions elicit a strong reaction from international public opinion. If there is no such reaction, the perpetrators know they can continue their plan in front of passive witnesses.

To prevent this stage from occurring, international military intervention is necessary if support can be mobilized from superpowers, regional alliances, the UN Security Council, or the UN General Assembly. Humanitarian assistance from the UN or other organizations is also necessary.

How does this person’s story illustrate response to the particular stage of genocide in Dr. Stanton’s theory?

Peter’s family escaped from Germany when fled when the harassment and persecution of Jews became more frequent and severe. Peter’s father experienced this personally. He was attacked and badly beaten by an antisemitic mob of his former colleagues.

By 1943, the majority of Dutch Jews, who were less aware of the danger than Jews who had fled Germany and Eastern Europe, had been deported to concentration camps and from there, to the Auschwitz and Sobibor extermination camps. Under the impending threat of deportation, Peter’s parents had to make the impossible decision of going into hiding and separating from their infant son. In hiding, all three suffered hunger, illnesses and betrayal by Dutch collaborators.

The silence of the majority of the Dutch population and the collaboration of the Dutch state apparatus allowed the persecution to thrive in the Netherlands, resulting with 75% of its Jews murdered, the highest number in Western Europe.